One of the goals of our work here at Wisdom Voices is to remember and highlight the work of progressives who have walked before us. Too often we forget – or never learned about –the lives of those who worked tirelessly to leave the world a better place for those who follow.

April, and its honoring of Earth Day, becomes the month we often focus on environmentalists history. So, this month we feature the life and work of Rosalie Edge, a progressive New York socialite and suffragist who took on the role of environmentalist and conservationist when she was in her 50s.

“Hellcat” and “Joan of Arc” were names used to describe the woman who served as the environmental link between John Muir and Rachel Carson. In fact, Carson cited the research she did at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (Edge’s most widely remembered accomplishment) as critical to the publication of Silent Spring.

Mabel Rosalie Barrow was born November 3, 1877, to a prominent New York family. Her father, a first cousin of Charles Dickens, instilled in Rosalie a love of writing and of the outdoors. She married Charles Edge in 1909 and the early years of their marriage were spent traveling abroad. It was during these treks that Rosalie was introduced to the early British suffragette movement. Eventually Edge immersed herself with the New York State Suffrage Party and quickly learned the importance of organizing and pamphleteering as key elements of a social movement. She also came to understand the importance of story telling as a vital tool to advance the cause of social justice. All of these would serve her well later in live as an environmental activist.

It wasn’t until adulthood that Rosalie began in earnest with bird watching in Central Park. In her later years she reflected that joy of birds may have come “as a solace in sorrow and loneliness” and that it gave “peace to some soul wracked with pain.”

It was in August 1929 that Edge’s new conservation career took focus while touring Europe. When mail arrived at her hotel in Paris, she was taken aback by a 16-page pamphlet: A Crisis in Conservation, written by Willard Van Name. Published several months earlier, the pamphlet set forth the danger that existed regarding the extinction of many North American birds. However, it was more than the impending crisis of bird survival that caught Edge’s eye. The greater shock conveyed by the pamphlet lay in its descriptions of the slaughter practiced and condoned by groups of sportsmen – and sanctioned by the National Association of Audubon Societies (now the National Audubon Society). It was that charge that most aroused Edge and prompted her return to the United States to take on the “establishment” of the then conservation movement.

“When we suffrage women attacked a political machine, we called out its name, and the names of its officers, so that all could hear. We got ourselves inside the recalcitrant organization, if possible, and stood up in meetings,” Edge wrote. And that’s just what she did. Edge attacked the “establishment” Audubon Society without a moment’s hesitation. She created a “conservation revolution” that focused more on the need to protect all species of birds and animals while they were common so that they did not become rare. She also asserted that it was every person’s civic duty to protect nature, working through the legislative process to achieve this. This was a dramatic shift from the standard thinking and practice in conservation.

Edge created the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), designed to reform the Audubon Association. She drew upon her suffragette background to create pamphlets, newsletters and press releases to develop a “clearing house” of publications with information about the natural work that could educate the bird-loving constituency that “did not come through the barrel of a gun.” It was during this time that she developed a profound professional relationship with Van Name.

Edge would later write about her encounter with Van Name and what they accomplished:

“How could I know that this simple suggestion was to change my whole life, to absorb my attention almost daily for the next 30 years and more to force me to study in fields that I had never distantly approached? It is so that our lives are changed in one moment. We get up in the morning unable to foresee the immensity of the day’s decisions and to go to bed at night, our destiny directed in an opposite direction. Some people say that this is done by the hand of God. In my case, it was the hand of Willard Van Name.”

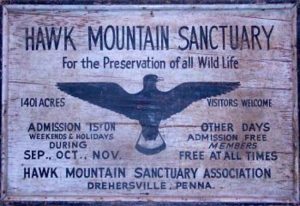

The two worked unceasingly on many measures, but none more so than the creation of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, on a ridge in the Appalachian Mountains in eastern Pennsylvania. In 1929, the Pennsylvania Game Commission offered a $5 bounty for every goshawk shot, as the birds of prey were considered to be pests. Hawk Mountain was a vital stop on a hawk migration route.

The two worked unceasingly on many measures, but none more so than the creation of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, on a ridge in the Appalachian Mountains in eastern Pennsylvania. In 1929, the Pennsylvania Game Commission offered a $5 bounty for every goshawk shot, as the birds of prey were considered to be pests. Hawk Mountain was a vital stop on a hawk migration route.

In 1932, an amateur photographer named Richard Pough shocked the wildlife preservation community with a series of photos of dead and dying hawks, shot by hunters both for sport and, theoretically, to protect barnyard fowl at surrounding farms. Edge wrote in response, “Man hates any creature that kills and eats what he wishes to kill and eat. He does not take into account the millions of rodents and insect pests that hawks consume.”

With financial assistance from Van Name, Edge in 1934 leased 1,400 acres on Hawk Mountain. She eventually purchased the land outright and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary was formed. Over the next three decades, Edge guided the sanctuary as president, raising money and initiating conservation programs.

It should be noted that Edge’s conservation work occurred during the arrival of the New Deal in Washington. Franklin Roosevelt’s commitment to conservation and his appointment of Harold Ickes as the new Secretary of the Interior brought a new wind of good fortune to the burgeoning conservation movement.

In addition to founding the ECC and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Edge led the national grassroots campaigns to create Olympic National Park (1938) and Kings Canyon National Park (1940), and successfully lobbied Congress to purchase about 8,000 acres of old-growth sugar pines on the perimeter of Yosemite National Park that were to be logged. She influenced founders of The Wilderness Society, The Nature Conservancy, and Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). Although the ECC was superseded by these larger conservation organizations, Edge held tight to her reign at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary well into her 80s. She died November 20, 1962.

For more information on Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and Edge click here.