Immigration issues. Women’s rights. Evangelicals taking control of he Republican Party. Creationism vs. science. Wealth inequality. And the issue of the day that would not disappear from the headlines—a “living wage” for the working class of this country.

Think were talking about 2013? Think again. Just over a century ago those topics screamed and streamed in the only real social media of the day—the newspaper. The political and social concerns facing us now are in reality “nothing new.” And it would serve us well to occasionally revisit the progressive voices who fought for social and economic justice generations ago. To reflect on the how and why we find ourselves “condemned to repeat” history when we forget what it is we could learn from it would also be a good thing.

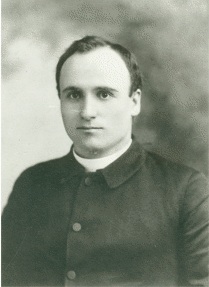

A Living Wage. Distributive Justice. We talk of them today as if they were never with us before. Yet, those two topics served as the basis for some of the most important documents and discussion papers to surface in the early 20th century. Those are the titles of two essays/books written by Catholic priest, John A. Ryan, who was considered to be the foremost social justice advocate of his day. Yes, for many of us today, it’s hard to imagine a Catholic Church focused on social justice, but that was indeed the cry of many within an American Catholic Church taking shape during a time of the overwhelming wave of immigration to this country from the 1880s through to the early 1920s. Catholic immigrants faced persecution and discrimination on many fronts by those who saw these immigrants as somehow “un-American” or “different.” Abuse of immigrant workers was the norm; child labor laws didn’t exist. It was within this backdrop that Ryan, the son of an Irish immigrant farmer from Minnesota, wrote about moral principles and economic facts. Ryan’s family life formed many of his views on politics and society. Ryan’s childhood experience with the challenges faced by farmers formed his early investment in economic justice and the role of the Catholic Church in promoting social change.

After entering the seminary and studying further at the Catholic University in Washington, D.C., his Ph.D. dissertation A Living Wage became an influential economic and moral argument for minimum wage legislation in this country. In it, Ryan argues that every man, because he is “endowed by nature or rather by God, with the rights that are requisite to a reasonable development of his personality,” has a natural right to share in the earth’s products. The primary natural right to subsist on the bounty of the earth exists at all times; in an industrial society that right takes the form of a living wage. Subsistence, a bare livelihood, is the product of man’s right to life; a “decent livelihood” is demanded by man’s dignity.

Ryan advocated a legal minimum wage when there was none; indeed, he drafted the legislation for Minnesota, which, though slightly modified from his original version, became law in 1914. The Minneapolis Tribune reported at the time that Ryan and soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis were the two leading social reformers in the United States. Ryan also pushed for federal legislation on a range of basic employee rights, from the right to unionize to unemployment insurance. In 1919, he authored the Bishops’ Program for Social Reconstruction, which advocated for these measures as well as for public housing, a national employment service, and regulation of public utility rates, and monopolies.

He published another major piece, Distributive Justice: The Right and Wrong of Our Present Distribution of Wealth, in 1916. Based on his interpretation and understanding of Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (“Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor”) and extensive study of several plans for the reconstruction of post war societies, it was said that Distributive Justice served as the blue print for Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Ryan’s voice remained strong during the Progressive Era that marked the first decades of the 20th century and during the more conservative1920s when reform often was compared to socialism or communism. Ryan’s closeness to FDR and the New Deal both personally and politically garnered him the nickname “Right Reverend New Dealer.”

We continue today to struggle to bring a living wage to today’s workers. Not only here in the United State, but globally. What we need is a heavier discussion on the moral component on the 21st century gilded age that dominates our society today. One great moral voice today is Sister Simone Campbell. Read one of her many brilliant pieces on the topic of a living wage here. And Leo Gerard, International President, United Steelworkers, is one of the strongest advocates for workers today. John Ryan’s name surfaced again last year when another Ryan from Wisconsin dominated headlines. A recent account took a look at the Ryans in the news 100 years apart.

It’s good to remember and reflect on the son of an Irish immigrant who more than 100 years ago combined moral and economic justice theories to lead the way for us today. Excerpted below are samples from his Living Wage and Distributive Justice works. An educated and thoughtful writer with a command of the English language, Ryan provides great detail on the moral argument for a living wage, grounded in Catholic anti-individualism and natural rights traditions, to fight for the “indestructible right” to a living wage.

“When any man who is willing to work is denied the exercise of this right, he is no longer treated as the moral and juridical equal of his fellows. He is regarded as inherently inferior to them as a mere instrument to their convenience; and those who exclude him are virtually taking the position that their rights to the common gifts of the Creator are inherently superior to his birthright…The validity of needs as a partial rule of a wage justice rests ultimately upon three fundamental principles regarding man’s position to the universe. The first is that God created the earth for the sustenance of all His children; therefore, that all persons are equal in their inherent claims upon the bounty of nature…The second fundamental principle is that the inherent right of access to the earth is conditioned upon and becomes actually valid through the expenditure of useful labour…The two foregoing principles involve as a corollary a third principle; the men who are in present control of the opportunities of the earth are obliged to permit reasonable access to these opportunities by persons who are willing to work. In other words, possessors must so administer the common bounty of nature that non-owners will not find it unreasonably difficulty to get a livelihood. To put it still in other terms, the right to subsist from the earth implies the right to access thereto on reasonable terms.”

“On what ground is it contended that a worker has a right to a decent livelihood, as thus defined, rather than to a bare subsistence? On the same ground that validates his right to life, marriage or any of the other fundamental goods of human existence. On the dignity of personality. Why is it wrong and unjust to kill or maim an innocent man? Because human life and the human person posses intrinsic worth; because personality is sacred. But the intrinsic worth and sacredness of personality imply something more than security of life and limb, and the material means of bare existence. The man who is not provided with the requisites of normal health, efficiency, and contentment lives a maimed life, not a reasonable life…Furthermore, man’s personal dignity demands not merely the conditions of reasonable physical existence, but the opportunity of pursuing self perfection through the harmonious development of all his faculties. …”

“Thus far, the argument has been based upon individual natural rights. If we give up the doctrine of natural rights and assume that the rights of the individual come to him from the State, we must admit that the State has the power to withhold and withdraw all rights from any and all persons. Its grant of rights will be determined solely by consideration of social utility. In the concrete this means that some citizens may be regarded as essentially inferior to other citizens, that some may properly be treated as mere instruments to the convenience of others. Or it means that all citizens may be completely subordinated to the aggrandizement of an abstract entity, called the State. Neither of these positions is logically defensible. No group of persons has less intrinsic worth than another; and the State has no rational significance apart from its component individuals.”

“…his right to a decent livelihood in the abstract means in the concrete a right to a living wage. To present the matter in its simplest terms, let us consider first the adult male labourer of average physical and mental ability who is charged with the support of no one but himself, and let us assume that the industrial resources are adequate to such a wage for all members of his class. Those who are in control of the resources of the community are morally bound to give such a labourer a living wage. If they fail to do so they are unreasonably hindering his access to a livelihood on reasonable terms…Unlike the business man, the rent receiver, and the interest receiver, the labourer has ordinarily no other means of livelihood than his wages. If these do not furnish him with a decent subsistence, he is deprived of a decent subsistence.”